The Body in Question by Jill Cement

This book is short and emotionally intense (as many of my favorites are–either that or epically sprawling). Two people, identified only by their numbers (at first), are on a sequestered jury for a murder trial (committed, incidentally, by one of a pair of twins, although which one actually did it is a primary question). He is an anatomy professor; she is a married photographer. It’s a jury of only six, with the others identified just by vaguely descriptive nicknames (cornrows; the church lady; the alternate).

This book is short and emotionally intense (as many of my favorites are–either that or epically sprawling). Two people, identified only by their numbers (at first), are on a sequestered jury for a murder trial (committed, incidentally, by one of a pair of twins, although which one actually did it is a primary question). He is an anatomy professor; she is a married photographer. It’s a jury of only six, with the others identified just by vaguely descriptive nicknames (cornrows; the church lady; the alternate).

The, after the verdict, there’s a whole second section of fallout in their real lives with names, and t’s dark and tense and deeply ironic, with exploration of life, death, and inhabiting a body. In fact the drama is so perfect that it verges on unbelievable, but by that point I’m not sure true realism is what I want; it’s satisfying like this.

Bonus points for accurate legal trappings.

A lot of people have compared this to a Jonathan Franzen novel, which I think is usually intended as a compliment. I totally see it–they share the sense that they fully understand the complete psychology of all of their characters, which to me is both arrogant and a sign that the characters are insufficiently complex. Do they really think that people can be figured out like that? They also both write about characters’ less sterling moments, even from within their own points of view, with an unappealing air of contempt. Maybe a character is illustrating something, but she isn’t really living it.

A lot of people have compared this to a Jonathan Franzen novel, which I think is usually intended as a compliment. I totally see it–they share the sense that they fully understand the complete psychology of all of their characters, which to me is both arrogant and a sign that the characters are insufficiently complex. Do they really think that people can be figured out like that? They also both write about characters’ less sterling moments, even from within their own points of view, with an unappealing air of contempt. Maybe a character is illustrating something, but she isn’t really living it. This was certainly unexpected as a follow-up to The Tiger’s Wife. Set largely in the Arizona Territory in the 19th century, it has two alternating storylines that we imagine throughout surely somehow must intersect, although it takes a long time to learn how. One is Nora, a frontierswoman in the midst of a crisis that unfolds over approximately 24 hours, and the other is Lurie, whom we follow as an outlaw from about age 6, who joins a group of cameleers (yes, camels, in the western US, and this is all based on meticulous historical research), and addresses all of his sections to his camel, Burke.

This was certainly unexpected as a follow-up to The Tiger’s Wife. Set largely in the Arizona Territory in the 19th century, it has two alternating storylines that we imagine throughout surely somehow must intersect, although it takes a long time to learn how. One is Nora, a frontierswoman in the midst of a crisis that unfolds over approximately 24 hours, and the other is Lurie, whom we follow as an outlaw from about age 6, who joins a group of cameleers (yes, camels, in the western US, and this is all based on meticulous historical research), and addresses all of his sections to his camel, Burke. I really couldn’t put this down, which is saying a lot in a book that’s essentially a domestic drama. I was fascinated by the structure–it covers nearly a whole lifetime but without feeling rushed or diffuse. There is a definite telling, a consistent narrator who filters as he recalls, and a lightly drawn occasion for telling. The narrator dips in and out of timeframes as needed to tell his story, and it is never jarring or confusing.

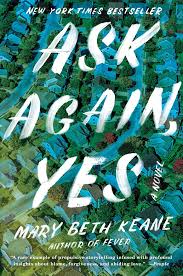

I really couldn’t put this down, which is saying a lot in a book that’s essentially a domestic drama. I was fascinated by the structure–it covers nearly a whole lifetime but without feeling rushed or diffuse. There is a definite telling, a consistent narrator who filters as he recalls, and a lightly drawn occasion for telling. The narrator dips in and out of timeframes as needed to tell his story, and it is never jarring or confusing. Two cops starting out in New York in the 70’s who then move to the same suburb–and what we get is the story of what happens over the next 30-40 years.

Two cops starting out in New York in the 70’s who then move to the same suburb–and what we get is the story of what happens over the next 30-40 years. Books that describe truly horrible and traumatic things, especially that happen to children, can be so challenging–to write and to read. (I think of A Little Life). And books that address major societal issues, like our history of racism, likewise. I think in both cases a book succeeds by being sufficiently personal, which this one is.

Books that describe truly horrible and traumatic things, especially that happen to children, can be so challenging–to write and to read. (I think of A Little Life). And books that address major societal issues, like our history of racism, likewise. I think in both cases a book succeeds by being sufficiently personal, which this one is. This is a perfect example of the kind of book I’ve started lovingly calling “quiet books.” There is absolutely nothing flashy going on; the writing is gorgeously simple, unadorned but breathtakingly accurate. No gimmicks, not even much of a plot–but just heartbreaking. Julian Barnes writes sort of like this, at times.

This is a perfect example of the kind of book I’ve started lovingly calling “quiet books.” There is absolutely nothing flashy going on; the writing is gorgeously simple, unadorned but breathtakingly accurate. No gimmicks, not even much of a plot–but just heartbreaking. Julian Barnes writes sort of like this, at times. The first thing that comes to mind to describe this book is “messy.” Not in a bad way–it’s well written, and the narrative is organized–but the life it describes is messy.

The first thing that comes to mind to describe this book is “messy.” Not in a bad way–it’s well written, and the narrative is organized–but the life it describes is messy. I would generally classify this as a not-too-deep, not-overly-literary, entertaining, historical (1940s), and at times slightly racy coming-of-age novel. The ingenue moves to New York City and discovers sex and the theatre scene; trouble ensues. And probably 2/3 of the book was just that.

I would generally classify this as a not-too-deep, not-overly-literary, entertaining, historical (1940s), and at times slightly racy coming-of-age novel. The ingenue moves to New York City and discovers sex and the theatre scene; trouble ensues. And probably 2/3 of the book was just that. I resisted this book for a long time, even as it got popular, largely because the only reasonable answer to the question of what the book is about is “trees.” While there is, ultimately, a plot, what really ties it together is thematic — and it’s a capital-I Issue at that — something so difficult to execute successfully that I tend to avoid those types of books altogether. But I ended up enthralled.

I resisted this book for a long time, even as it got popular, largely because the only reasonable answer to the question of what the book is about is “trees.” While there is, ultimately, a plot, what really ties it together is thematic — and it’s a capital-I Issue at that — something so difficult to execute successfully that I tend to avoid those types of books altogether. But I ended up enthralled.